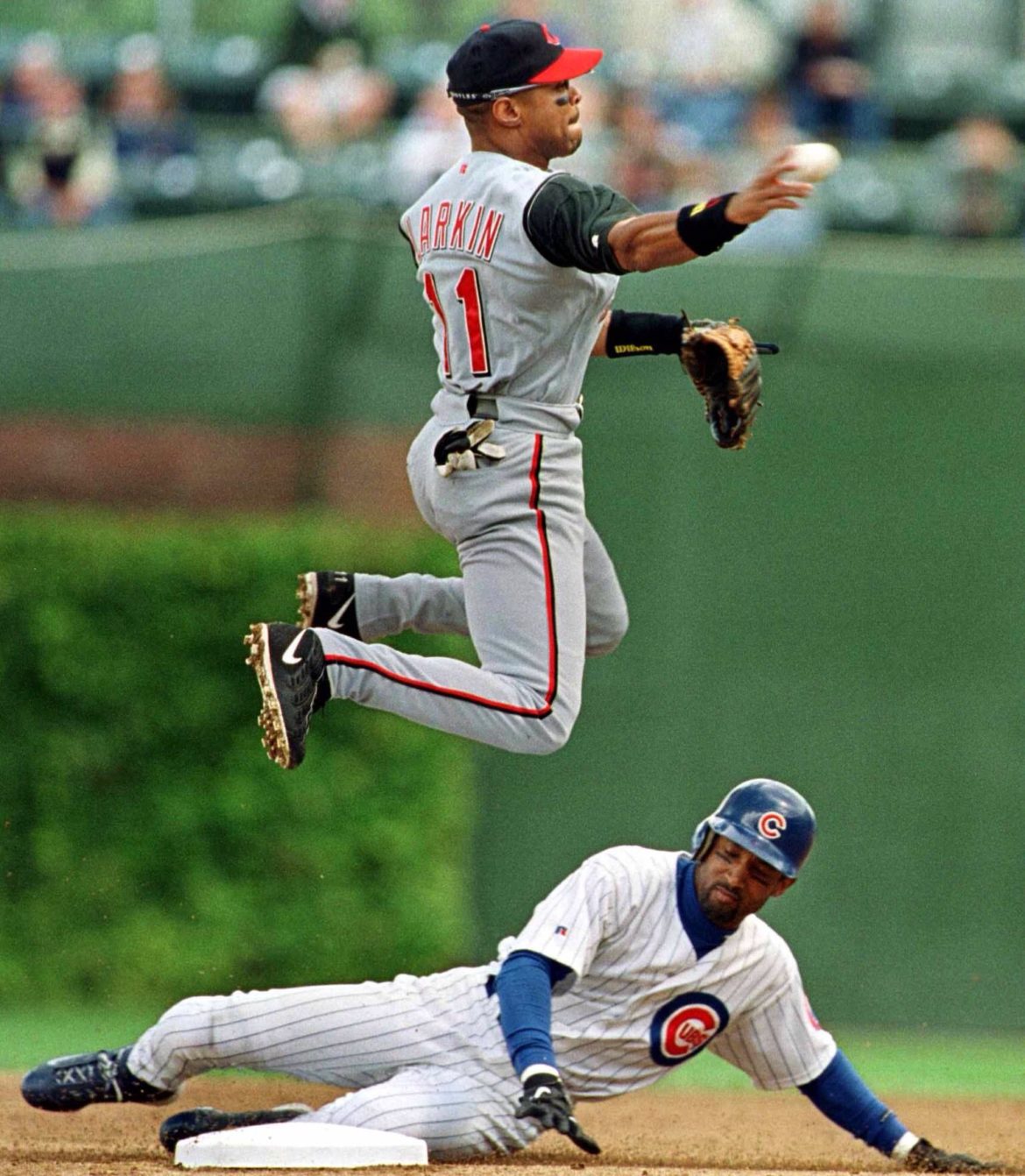

(This Diamond Nation Magazine cover story ran in 2012, a couple months before Barry Larkin was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Larkin graciously chatted with our writer by phone as he prepared for a trip to South America to promote the game of baseball. The Cincinnati Reds retired Larkin’s No. 11 a month after his Hall of Fame induction).

By Bob Behre

Barry Larkin was at home with his wife and one of his two daughters on the afternoon of Jan. 9, 2012 when he did a simple math equation in his head.

“It’s not going to happen,” he thought.

The Baseball Hall of Fame vote was to be released that afternoon and Larkin believed if he had been selected, he would have gotten word by then. It was almost 3 p.m.

“I was privy to some information on the process the public is not,” said Larkin, an analyst at the time for ESPN’s “Baseball Tonight.” “I knew the timelines for the day and thought it had already passed for me.”

Then the phone rang.

“I was surprised. Stunned,” said Larkin. “It’s such a lofty ideal to be a Hall of Famer. I thought, this can’t happen. I couldn’t even fathom it. I have so much respect for what it means and for the players in it. Babe Ruth is in the Hall of Fame. Jackie Robinson is in the Hall of Fame.

“I don’t consider myself worthy of that. I’m not that caliber of player. It was shocking when it all came down.”

Larkin’s career numbers, taken individually, don’t elicit awe, however he was an outstanding shortstop with offensive numbers that put him among the elite at that position.

Baseball historian and statistical expert Bill James has called Larkin one of the greatest shortstops of all time, ranking him No. 6 all-time in his “New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract.”

The baseball writers thought so, too, electing Larkin in his third year of eligibility and with 86.4 percent of the vote. He would be inducted Sunday, July 22 on the grounds outside of the Clark Sports Center in Cooperstown, New York.

Wildly popular Chicago Cubs third baseman Ron Santo, elected posthumously by the Veterans Committee, entered the Hall of Fame with Larkin. Santo died in December of 2010.

Larkin finished his 19-year career, all with the Cincinnati Reds, with a .295 batting average, hit 198 home runs, drove in 960 runs, scored, 1,329 runs, stole 379 bases and had 2,340 hits.

His many other accomplishments seem even more significant. He was National League MVP in 1995; batted .353 in helping to lead the Reds to the 1990 World Series title; made 12 All-Star Game appearances, and received three Gold Gloves at a time Ozzie Smith was still in the league.

“I didn’t consider myself great at any one thing but I was good at a lot of things,” said Larkin. “The years I hit 30 home runs, they weren’t pitching to the guys behind me in the lineup, they were pitching to me. My best years I had guys like Kevin Mitchell and Ron Gant hitting behind me in the lineup.”

That humbly said, Larkin was considered among the very best of his era. Larkin, in 1988, struck out a miniscule 24 times in 588 at bats. He hit five home runs in two games in 1991, the first shortstop to do so. He became the first shortstop to join the 30-30 Club when hit 33 home runs and stole 36 bases in 1996.

Larkin also won nine Silver Slugger awards, presented annual to the top offensive player at each position.

Those who saw Larkin play every day had no doubt about his Hall of Fame qualifications.

“I’d be shocked if Barry doesn’t get in this year,” Jim Bowden, Larkin’s general manager with the Reds, told USA Today four days before the vote was announced. “If he doesn’t get in, I’m going to resign from all of my jobs. That’s how confident I am.”

Ken Griffey, Jr., a teammate during the final five years of Larkin’s career, was quoted recently saying, “To me, Barry changed the way teams drafted shortstops. There were no Alex Rodriguezes when he came along. No Derek Jeters. No Nomar Garciaparras. You used to get these short, little guys who would hit eighth and just slap it. Barry changed all that. Shortstops aren’t batting eighth anymore. They’re batting 2-3-4-5.”

All the statistical and team achievements aside, Larkin points to certain intangibles that enabled him to play at a high level for so many years.

“I had some really good people who influenced me early in my career,” he said. “They gave me perspective. That was important.” Larkin’s Reds teammate Eric Davis is certainly one of those people who provided that valuable perspective.

“When we first met, Eric invited me and my family to stay with him in California in the off-season. He opened his home to me, my wife and two young daughters and showed me how it was done in the off-season.”

Larkin points to Davis, too, for lifting the Reds on his back in the 1990 World Series, a World Series that was supposed to be a coronation for the mighty Oakland Athletics.

“Eric was a guy who brought people to together,” said Larkin. “He’s was the only guy on the team with street cred’, if you would. He said, ‘this is how we do it and this is how it goes down. I got your back.’ He was the man.”

Davis hit a home run in the first inning of Game 1 against the Athletics that many feel provided the spark for the Reds’ unlikely four-game sweep. “Eric believed we were going to win and the rest of us believed it, too, because of him.”

Larkin’s humble nature and deference to teammates is perhaps best exhibited by his decision to learn the Spanish language to get closer to those teammates who only spoke Spanish.

“I thought it would be a way for me to communicate a little better with those guys,” said Larkin. “Coming up through the minors I met a lot of guys who couldn’t speak the language very well. They were making a transition. It was a culture shock for them.”

Larkin and his teammates used the Spanish language as an advantage on the field to pick more than a few runners off base.

Larkin won the Roberto Clemente Award in 1993, presented each year since 1971, to the player who best exemplifies the game of baseball, sportsmanship, community involvement and an individual’s contribution to his team.

He won the Lou Gehrig Memorial Award the following year. That honor has been presented, each year since 1955, to the player who best exemplifies Gehrig’s character and integrity both on and off the field.

Larkin’s post-playing days have been noted for his work with the MLB Network and ESPN but his broadcasting jobs are a small part of his new life around the sport.

“Barry really is an ambassador for baseball,” says Keith Dilgard, president and general manager of Diamond Nation in Flemington, New Jersey. “He has created a worldwide initiative to improve skills in the game and teach it the right way, the way he learned it at the MLB level.”

Larkin was in Brazil and Ecuador for two weeks in February, 2012 speaking the baseball gospel.

“It was a baseball-centric trip,” said Larkin. “I’m working with MLB International. We run a camp in Brazil for 14-17 year-olds. We’re trying to get them to improve their development in the sport and get them draft-eligible. We are trying to globalize the sport.”

The camp environment gives Larkin a chance to give back to the game.

“It’s very rewarding,” he said. “Working with and interacting with kids is great. There is great enthusiasm out there and kids want to learn. There will be a language barrier in Brazil because I don’t speak Portuguese. But baseball’s language is global.”

One trip Larkin never made was one that seemed destined in July of 2000 when the Reds and Mets had agreed to a trade that would send the shortstop to New York. But potential free agent Larkin, with 5-and-10 rights, short-circuited the trade when then-Mets general manager Steve Phillips wouldn’t agree to give him a three-year contract.

“I was unwilling to uproot my family,” he said. “I would have been a rental player with an unsure off-season.”

Larkin did love playing at Shea Stadium, so much that he named one of his daughters, Brielle D’Shea. “I loved Shea, the roar of the jets overhead. Growing up I wanted to be a fighter pilot. All those jets roaring overhead fired me up and the crowd always energized me.

“And I always loved the Mets fans getting on me, good or bad. I had a good relationship with them. There was a group of guys near the on-deck circle who’d greet me for years. It was a lot of fun.”

Larkin says the only regret he has about his playing career is that, “I wish I had more opportunities to play in the World Series.

“Individual accomplishments are just that. I had my share of those. The game is about winning championships. The ultimate goal is to be on the field when the last out of the season is made and you are No. 1. I was only able to stick up my finger once in my career and say, ‘We are No. 1.’”

On July 22, 2012 in Cooperstown, Larkin joined the very elite of baseball at the top of the heap.

Postscript: Larkin has stayed actively involved in the game since 2012. His name arose in managerial searches by Detroit (2013) and Tamp Bay (2014) but declined interviews due to his various responsibilities with the league. He was hired as a roving minor league infield instructor by the Reds in 2015 and helped out with the major league club in 2016. Larkin has remained involved with the Sports United Envoy program for the U.S. Department of State. He has traveled to Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, India, Lithuania and Taiwan where he worked conducting clinics in promoting the game worldwide.