In a recent interview with new Lafayette College coach Tim Reilly, we talk about the importance of educating yourself on the game of baseball. Reilly emphasized what a great time this is to do exactly that.

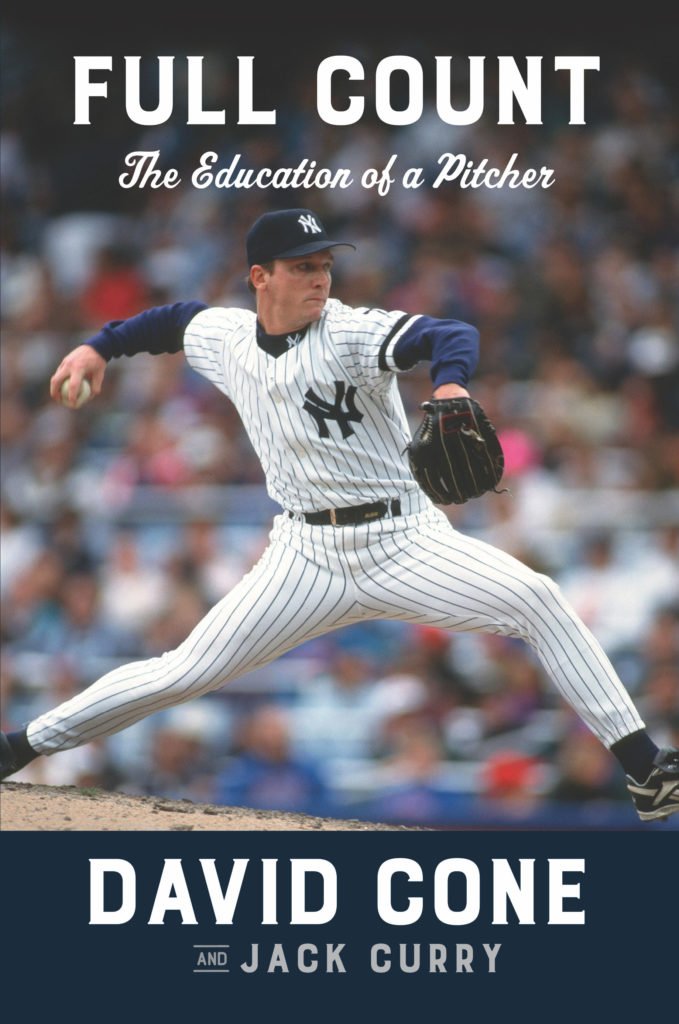

Despite my inability at this point in my life to get batters out, I decided to dissect the book co-written by former Yankees and Mets pitcher David Cone and YES Network reporter Jack Curry.

In Full Count, The Education of a Pitcher,” we learn that Cone is a connoisseur of every pitching nuance and, as a former player, someone who embraces the new wave analytics that has taken baseball by storm. For Cone it was, and still is, all about acquiring as much information as possible to improve your plan of attack on the mound.

Cone, indeed, was as ferocious in his pursuit of knowledge as he was in his thirst of getting outs on the mound.

Consider this less a review of an outstanding and instructive book than a sharing of an advanced placement course in pitching. But Cone and Curry make it easy for players and coaches to digest the knowledge they have to impart, regardless of whether you are a 12 year old or a veteran pitcher in ‘The Show.’ Sure some of it is over the head of Little Leaguers, but certainly not their coaches.

“Being a pitcher means being a creator, an improviser, and a magician, a person willing to devise some way to throw the ball so that the hitter is deceived and defeated,” Cone says. Deception would prove to be a theme running through Cone’s pitching story.

Confidence is a super-critical ingredient to a pitcher’s success, according to Cone, who believes pitchers tend to give batters too much credit.”

“In the competitive, evolving batter-versus-pitcher world, pitchers should be adamant about focusing on their strengths, not a batter’s weaknesses,” he says. “I much rather emphasize what I did well, not what the batter did well, which is what confident pitchers do.”

But for a pitcher to evolve to the point he is confident on the mound requires some success in getting batters out. Most young pitchers are given that opportunity at some point, particularly if they exhibit some arm strength as a young player.

Getting equally young batters out, they find, usually requires nothing more than a hard fastball and, if they must, changing speeds a bit. But while the competition improves as a player ages, pitchers require some real tools, physical and mental, to outwit the many good hitters they will encounter.

Cone gives excellent tips on the proper grips for two- and four-seam fastballs, cutters, curveballs, sliders and changeups; pitches that can be experimented with as young pitchers get older, bigger and stronger.

“Pitchers need to be students, forever students, because there’s always a chance to learn something or poach something that will make you better,” says Cone.

The poaching Cone refers to occurs organically as we watch other pitchers and learn what they do to get batters out. That process also includes applying tips from a variety of coaches you’ll meet along the way.

Cone points out, pitchers with a wealth of talent can stifle their own success due to confidence issues, which can cause them to pitch defensively instead of aggressively. Part of the process, he says, is learning to deal with failure.

“To develop and learn to be tougher, a player usually needs to get humbled and feel what it’s like to fail,” says Cone. “What is mental toughness for a player? It’s a mind-set, an approach, and a way of acting and reacting to the good, the unexpected, and the uncertain.”

Cone refers to the critical relationship a pitcher has with his catcher as “The Dance.”

“The best catchers understand that pitchers can be needy and selfish, and they also understand their advice might be shunned by the same pitchers who long to be in a partnership,” says Cone. “But those catchers keep trying to make the pitcher feel comfortable because that’s their job and that’s the best script for trying to win games. They keep dancing with the pitcher. One leading, one following, both of them working in unison.”

Most telling of Cone’s story is how he continually evolved as a pitcher, always willing to learn something new and find new ways to keep batters off-balance, guessing.

“I like stubborn pitchers because they fight for themselves,” he says, “and I like confident pitchers because they believe in themselves.”

Cone is certainly a great source to tap for pitching expertise and the equally important mental side of the discipline. He won 194 major league games while posting a 3.46 ERA and boasts 2,668 strikeouts over 17 seasons. His post-season experience, and success, provided plenty opportunities to pitch in high-pressure spots, which he relates in valuable detail.

Cone was 8-3 with a 3.80 ERA in 21 post-season appearances and won World Series championships with the 1992 Toronto Blue Jays and the 1996, ’98, ’99 and ’00 Yankees. He won 20 games twice and the Cy Young Award in 1994 with the Royals. And on July 18, 1999, Cone pitched a perfect game against the Montreal Expos, which made for a terrific chapter.

Curry was a Yankees beat writer for The New York Times for 20 years and, since 2010, does pre- and post-game analysis for the YES Network. He says he approached Cone to co-write the book because, “his creative mind made him the ideal pitcher for this book.”

Young pitchers would be wise to read “Full Count” and take notes along the way that they can apply on the mound.

Jim Bouton, who pitched for the Yankees in the 1963 and ’64 World Series and wrote the controversial book “Ball Four,” perhaps said it best about gripping a baseball.

“You spend a good piece of your life gripping a baseball and, in the end, it turns out that it was the other way around all the time.”